Material Point Method Simulation

Posted on Dec 10, 2019

During my fall semester of junior year in college, I took a course called CIS563: Physics-based Simulations. This course is taught

by Dr. Chenfanfu Jiang, whose research focuses on realistic physics-based simulations.

He is well known in the computer graphics community for utilizing the material point method in his research and projects.

Prior to taking CIS563, I had zero experience with computer graphics simulations, let alone physics-based. I have always wanted to

learn how those millions of leaves in the bridge to the Land of the Dead interact with each other in Coco, or how the snow in Frozen seems to have

a personality of its own.

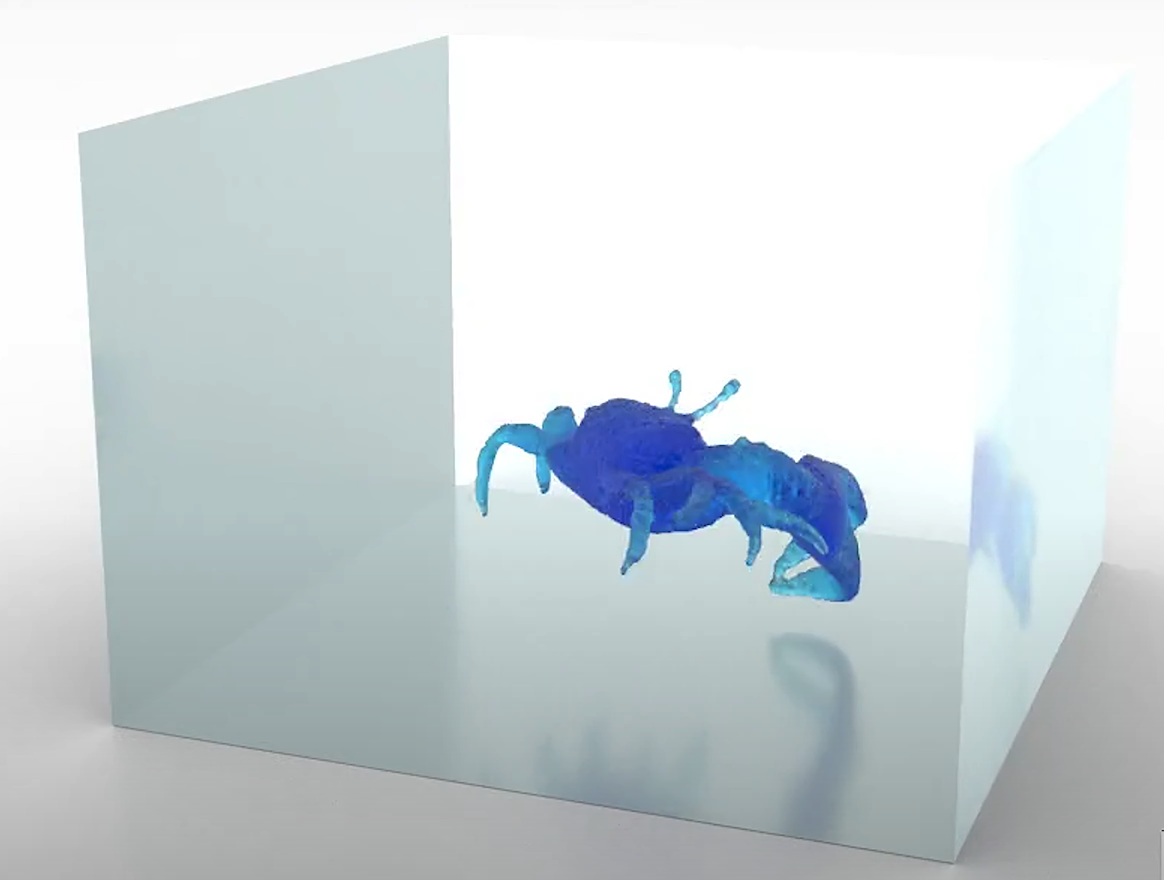

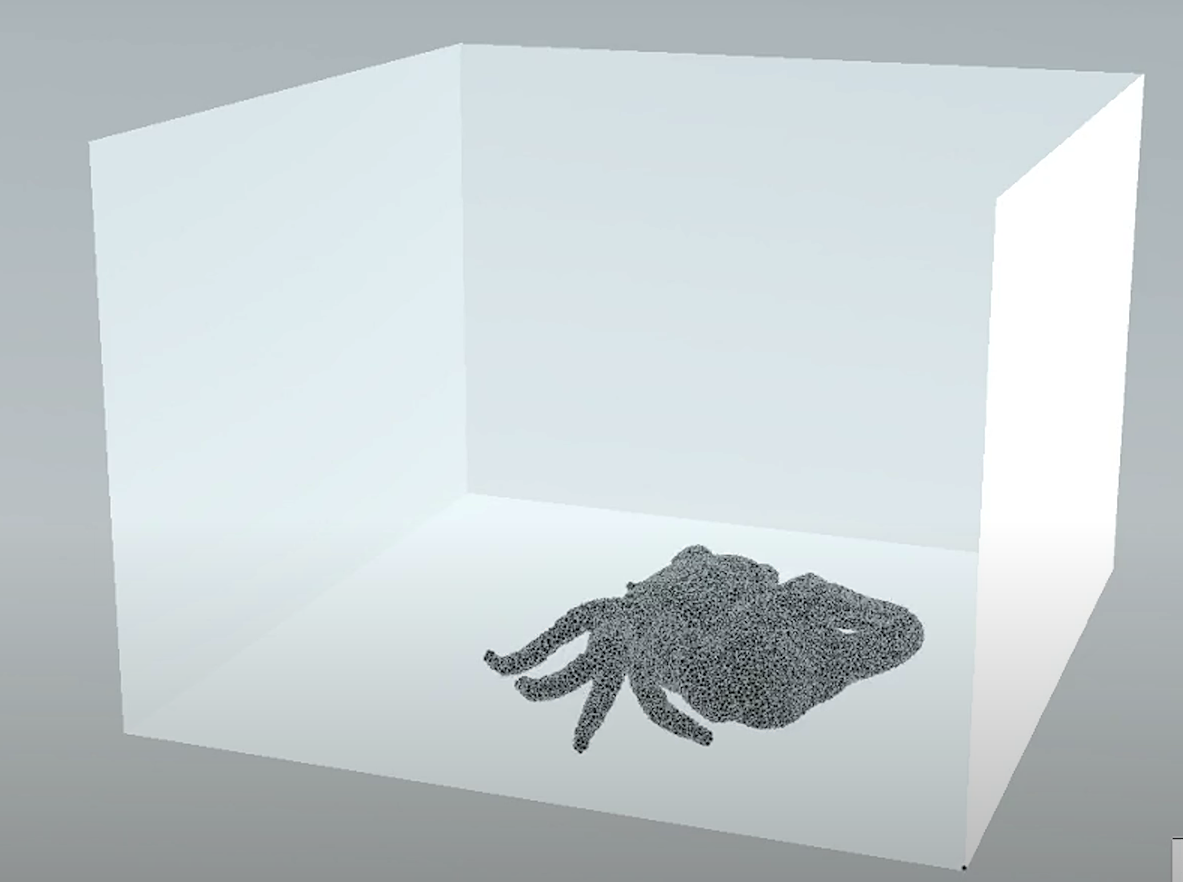

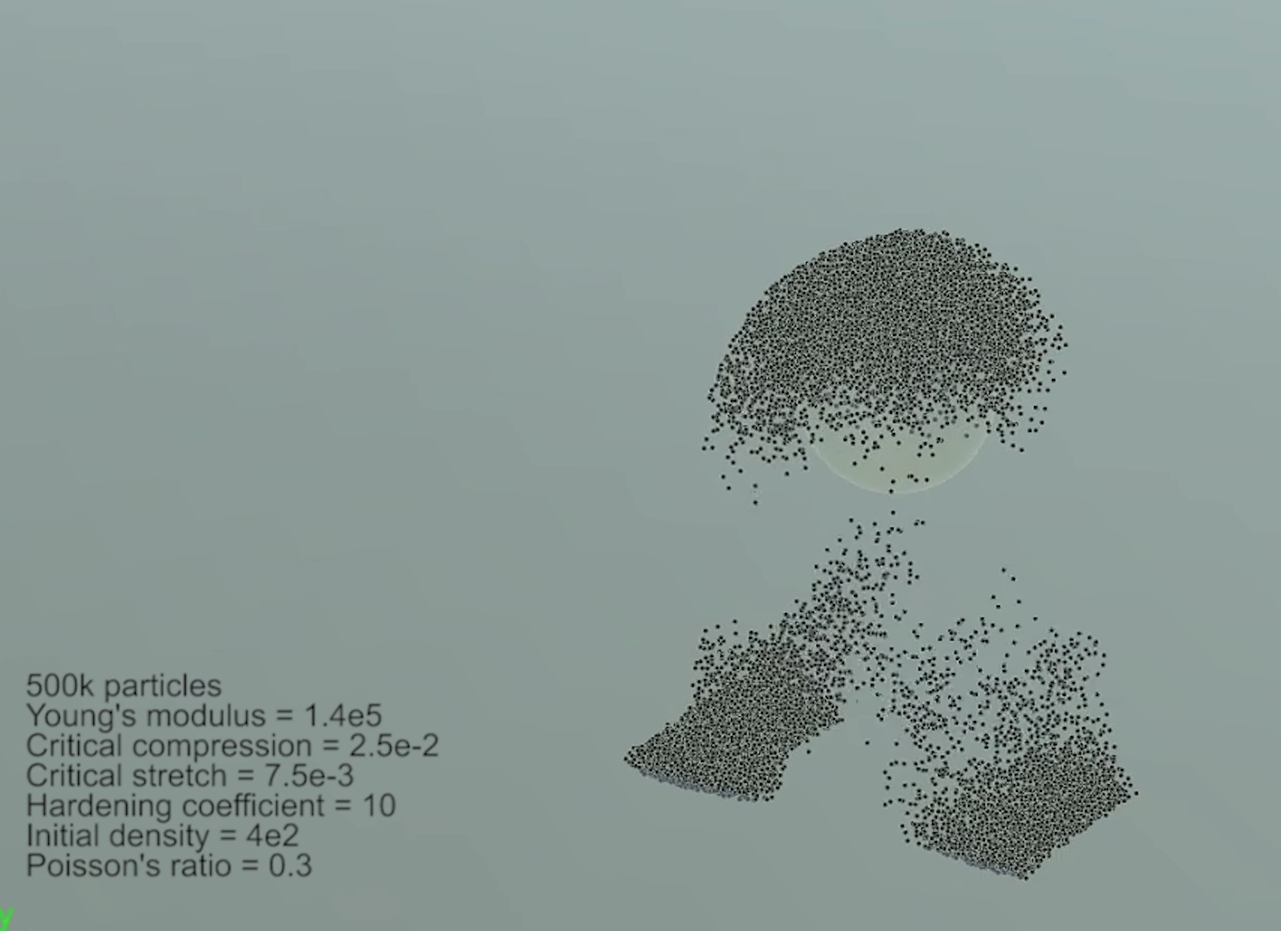

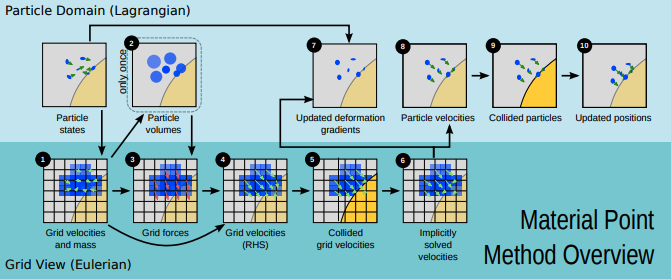

For the final project in the course, I created two different types of simulations using a method called Material Point Method (MPM).

There are lots of ways in which simulations can be done. Some methods represent objects as individual particles connected by spring like

edges and directly applies forces onto those particles. Other methods model objects with particle-voxel hybrid

(see Robert Bridson's book

on fluid simulations).

MPM is gaining popularity in the CG simulations community because it is fast, relatively easy to implement, and is pretty stable

for most material.

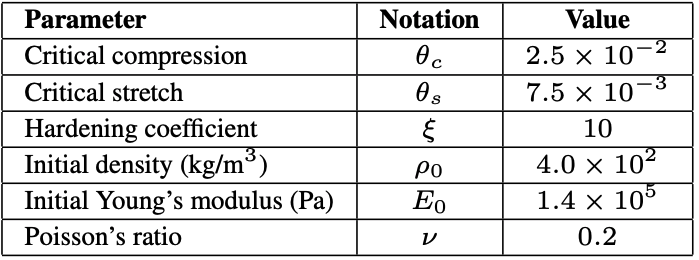

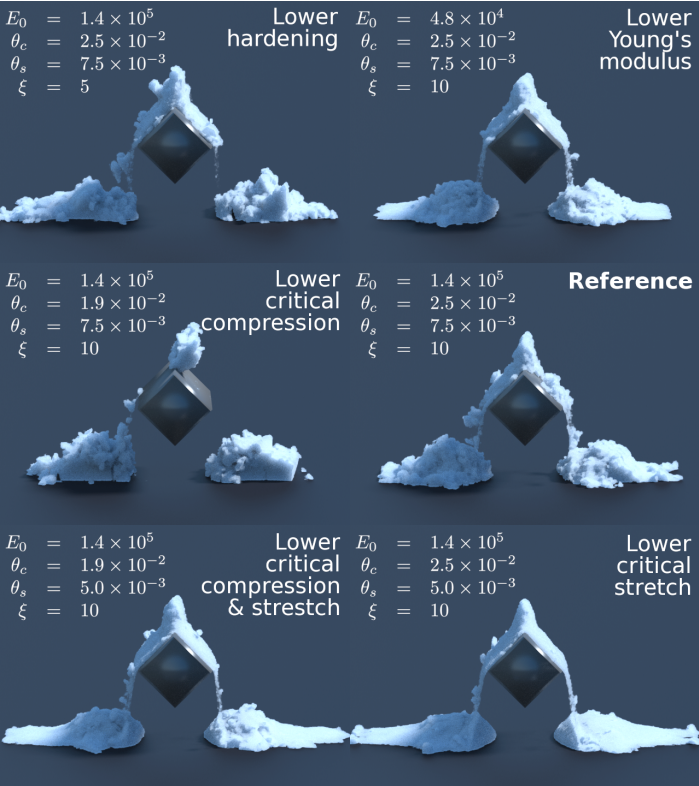

Using MPM, I created two different simulations - jelly-like material (elastic) and snow. First I outputed particle data for each frame, then transfer this particle information to Houdini using various Houdini nodes. In order to speed up the simulation output generation, I used Ubuntu (dual-booted on my 8GB RAM Macbook Pro 2017).